Ford’s ill-fated Edsel

Division was born in 1957 as part of an ambitious plan to match General

Motors division for division. Edsel died only two years later, but it

remained the butt of jokes for decades and its name became virtually

synonymous with failure. This week, we look at the history of Edsel and

the reasons it flopped.

MERCURY RISING

Today,

with car companies selling or shuttering divisions as fast as state

franchise laws will permit, it’s become fashionable to criticize the

auto industry — particularly General Motors — for its surfeit of brands.

For decades, however, GM’s divisional structure was the envy of

Detroit. Almost every automaker aspired to a GM-like brand hierarchy,

from Chrysler to upstart independents like Kaiser-Frazer.

Until the late thirties, a major exception was the Ford Motor Company. Although Ford had acquired bankrupt Lincoln back in 1922,

Henry Ford had never cared for expensive cars and he steadfastly

refused to create a mid-priced line. In the early years of the Great

Depression, that wasn’t much of a loss, but as the economy began to show

signs of life, the vast price gap between Ford and Lincoln cost the

company many buyers.

In the summer of 1937, Edsel Ford and sales

boss John R. Davis finally persuaded Henry to authorize the development

of a new mid-priced car. It emerged the following fall as the 1939

Mercury. Although the Mercury shared many components with the standard

Ford, including a bored-out version of the familiar flathead V8,

it was bigger, heavier, and more expensive, putting it in the same

territory as mid-priced makes like Oldsmobile, Hudson, and DeSoto.

The

Mercury sold reasonably well, but it was not a great threat to GM’s

mid-priced divisions. Its main failing was that most buyers perceived it

as a Ford, not a separate brand. Indeed, even Edsel Ford had wanted to

call it the Ford-Mercury and all of the early promotional material

carried that name. Most Mercurys were even sold through Ford dealers;

there were a few dealers who only sold Lincolns and Mercurys, but they

were rare before the war. The consequence was that each of Mercury’s

direct rivals outsold it by more than two to one.

HENRY FORD II AND THE WHIZ KIDS

By

the fall of 1945, Edsel Ford was dead and Henry Ford had reluctantly

ceded control of the company to Edsel’s eldest son, Henry Ford II. Henry

II, then only 27, realized immediately that the company’s problems were

beyond his ability, and sought outside help.

Shortly after

Henry’s ascendancy, he hired a group of young officers recently released

from the United States Army Air Force, including Charles “Tex”

Thornton, Ben Mills, Francis (Jack) Reith, and Robert McNamara.

All had

worked together in the Army Air Forces’ Office of Statistical Controls,

applying the latest techniques in business analysis to the war effort.

When the war ended, Tex Thornton sent an impudent telegram to Henry Ford

II, offering the group’s expertise to Ford.

The Whiz Kids, as

Thornton’s group became known, were smart, ambitious, and ruthless.

While they each aspired to top positions within Ford (which many of them

later achieved), many of them had little interest in cars or the auto

business for their own sake. Cars — and to some extent Ford itself —

were simply a means to an end.

Clever as the Whiz Kids were, they

were not much older than Henry Ford II, so Henry decided he needed more

experienced managerial help. In the summer of 1946, he hired Ernest R.

Breech, former president of GM’s Bendix subsidiary, as his executive

vice president. Breech, in turn, recruited a host of other GM veterans,

including Harold Youngren, Earle MacPherson, and Lewis Crusoe, who

became Ford’s VP of operations and later the general manager of the new

Ford Division. Unlike the Whiz Kids, who were after power, Breech’s

group sought to make over Ford in GM’s image. Their ultimate goal was to

do everything GM had done, only better — from management style to

divisional structure.

Inevitably, there was great tension between

the Whiz Kids and Breech’s group. Despite their youth, the Whiz Kids had

just spent three years telling generals what to do and had an

unshakable confidence in their own talents. They sometimes made a great

show of deference to Breech and other older executives, but privately,

they often regarded them as obstacles and adversaries.

Henry Ford

II watched these conflicts unfold, never permanently siding with any one

group. His only goal was to restore his grandfather’s company to its

former position as the world’s number-one automaker, and he was willing

to follow whatever path seemed likely to get him there. To some extent,

he may have been intimidated by the brilliant and driven men working for

him, but at the end of the day, it was Ford’s company.

The

1946-1948 Fords, Mercurys, and Lincolns were lightly refreshed prewar

designs; this is a 1948 Mercury station wagon. The 1949 models were

introduced quite early in 1948: The new Mercurys bowed on April 29,

almost six months earlier than usual.

The

1946-1948 Fords, Mercurys, and Lincolns were lightly refreshed prewar

designs; this is a 1948 Mercury station wagon. The 1949 models were

introduced quite early in 1948: The new Mercurys bowed on April 29,

almost six months earlier than usual.

POSTWAR FORDS, LINCOLNS, AND MERCURYS

Once

Henry Ford I was gone, no one at Ford had any compunctions about

expanding the company’s product line. Early plans called for an

extensive new lineup: a bigger standard Ford, a new compact “Light Car,”

two different Mercurys, and three Lincolns, the largest of which was to

replace the Continental as the company’s flagship.

With Ford’s

finances still shaky, however, those plans proved overly ambitious. The

Light Car was sent overseas to become the 1949 French Ford Vedette while

the bigger Lincolns were canceled. Ford launched a crash program to

design a new standard Ford, the bigger Ford became a Mercury, and the

larger Mercury became the base-model Lincoln.

When the all-new 1949 models finally appeared, the lineup was as follows:

- The Ford, on a 114-inch (2,896mm) wheelbase, priced in the $1,300-$1,900 bracket

- The Mercury, on a 118-inch (2,997mm) wheelbase, priced in the $2,000-$2,500 bracket

- The standard Lincoln, on a 121-inch (3,073mm) wheelbase, priced in the $2,500-$3,200 bracket

- The Lincoln Cosmopolitan, on a 125-inch (3,175mm) wheelbase, with prices ranging from just under $3,200 to about $4,000.

In

theory, the new model range gave Ford an entry in each major segment of

the American market. The Ford competed with Chevrolet and Plymouth; the

Mercury with Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and Dodge; the standard Lincoln with

Buick and Chrysler; the Lincoln Cosmopolitan with Cadillac and Packard.

In practice, there were still large price gaps between the different

model lines, the most problematic being the more than $500 gap between

Mercury and Lincoln. That was a lot of money at the time, so the gap

probably cost Ford a lot of middle-class customers. Marketing studies

revealed that only about one in four Ford buyers moved on to a Mercury

or Lincoln while more than four out of five Chevrolet buyers stepped up

to a more expensive GM car. Ford needed something to fill the gap.

The 1949-1951 Mercury was originally designed

by Bob Gregorie as the 1949 Ford, but Ernie Breech thought it would be

too big and cost too much to build for the low-priced field, so it

became a Mercury instead. Powered by a 255 cu. in. (4,184 cc) version of

the Ford flathead V8, it had 112 hp (84 kW) in 1951. The 1949-1951 Merc

was very popular with hot rodders and customizers, although its

straight-line performance was no match for that of the new Oldsmobile Rocket Eighty-Eight. (Photo © 2007 Späth Chr.; released to the public domain by the photographer)

The 1949-1951 Mercury was originally designed

by Bob Gregorie as the 1949 Ford, but Ernie Breech thought it would be

too big and cost too much to build for the low-priced field, so it

became a Mercury instead. Powered by a 255 cu. in. (4,184 cc) version of

the Ford flathead V8, it had 112 hp (84 kW) in 1951. The 1949-1951 Merc

was very popular with hot rodders and customizers, although its

straight-line performance was no match for that of the new Oldsmobile Rocket Eighty-Eight. (Photo © 2007 Späth Chr.; released to the public domain by the photographer)

THINKING BIGGER

In September 1948, only four months after the ’49s went on sale,

Henry Ford II ordered a study group to explore adding a new mid-priced

car between Mercury and Lincoln. Preliminary planning work started the

following year, but it was put on hold in the summer of 1950, following

the outbreak of the Korean War. The need hadn’t gone away, but with new

production restrictions and severe shortages of strategic materials,

Ernie Breech and the executive committee decided it was a bad time to

introduce a new car line.

In August 1951, Emmett Judge, the head of product planning for

Lincoln-Mercury, and Morgan Collins, Lincoln-Mercury’s controller,

appeared before the committee with a new proposal. They had recently

analyzed GM’s 1950 shared bodies program, which was one of the most

ambitious in the industry to date, and concluded that if Lincoln-Mercury

adopted a similar interchangeability program, they could save enough

money on tooling for their existing lines to finance a new model.

The Collins-Judge proposal was eminently logical, but it was

politically problematic. Various factions were busily wrestling for

control of product planning decisions, and the Collins-Judge plan, while

eminently sensible, satisfied none of these ambitions.

From 1949 to 1951, Lincoln offered both a

short-wheelbase base model (originally designed as a big Mercury) and

the bigger Cosmopolitan; this is a 1951 Cosmopolitan convertible. In

1952, Lincoln consolidated its line on a single chassis, sized between

the 1951 models. Since the cheaper model had accounted for more than

half of all Lincoln sales, this move proved to be a serious marketing

mistake. (Photo © 2008 Jagvar; released to the public domain by the photographer)

From 1949 to 1951, Lincoln offered both a

short-wheelbase base model (originally designed as a big Mercury) and

the bigger Cosmopolitan; this is a 1951 Cosmopolitan convertible. In

1952, Lincoln consolidated its line on a single chassis, sized between

the 1951 models. Since the cheaper model had accounted for more than

half of all Lincoln sales, this move proved to be a serious marketing

mistake. (Photo © 2008 Jagvar; released to the public domain by the photographer)

Nonetheless, the price-gap issue remained, so in January 1952, the

executive committee assigned sales VP John Davis to conduct a new study

on adding additional mid-priced models. Considering the work that had

already been done, there was little logical need for another study, but

it served as a sort of bureaucratic flanking maneuver, giving the

different factions a chance to spin the existing proposals their own

way.

The so-called “Davis Book,” a massive, six-volume treatise completed

in June 1952, outlined in great detail what most Ford executives had

already realized about the company’s position in the mid-priced market.

If anything, that problem had only gotten worse: With the demise of

Lincoln’s cheaper short-wheelbase model for 1952, the least-expensive

Lincoln now cost almost $1,000 more than the equivalent Mercury.

Although Ford chief engineer Earle MacPherson reportedly thought the

Lincoln should target the Oldsmobile Ninety-Eight, the Lincoln was

priced like a Cadillac, not an Olds or Buick. Mercury, meanwhile, lacked

the prestige and distinction to appeal to Buick or Chrysler buyers.

The Davis Book basically reiterated the recommendations of the

previous studies, proposing the creation of a new “big” Mercury

(described as “Mercury-Monterey”) combining the Lincoln body shell with

Mercury running gear. Davis added a new wrinkle by recommending that

Mercury and Lincoln be split into separate divisions and that Ford

introduce a new flagship model priced above existing Lincolns; the

latter was intended to answer dealer requests for a successor to the old

Continental. This flagship was to be built by a new Special Products

Division, which would increase the total number of Ford automotive

divisions from two four.

Henry Ford II reviewed these recommendations and assigned his younger

brother, William Clay Ford, to lead the development of the flagship

car. Lincoln-Mercury Division assistant general manager Richard Krafve

was assigned to develop the “Mercury-Monterey” concept, initially slated

for the 1956 model year.

BIRTH OF THE E-CAR

Despite two marketing studies and an obvious need, development of the

Mercury-Monterey proceeded surprisingly slowly. Styling work didn’t

begin until mid-1954, fully two years after the Davis Book.

According to

historian Tom Bonsall, many (though not all) of the Whiz Kids were

dubious about the upper-middle-class model, thinking it would cost too

much. Ford’s senior management, meanwhile, was preoccupied with early

preparations for Ford’s first public stock offering, which took place in

January 1956 and ultimately netted more than $640 million.

Until late 1954, the assumption was still that the new model would be

an upscale Mercury, offered through existing Lincoln-Mercury

franchises. However, a series of management changes in early 1955

changed those plans dramatically. In January, Ernie Breech was named the

chairman of Ford’s new board of directors.

Lewis Crusoe assumed some of

Breech’s former responsibilities with a promotion to group vice

president of car and truck operations; Robert McNamara took Crusoe’s

place as general manager of Ford Division. At the same time, Whiz Kid

Jack Reith returned to the U.S. after a stint as general manager of Ford

SAF, Ford’s struggling French subsidiary. Reith had just completed a

deal to sell Ford SAF to Simca, which was heralded as a

silk-purse/sow’s-ear achievement for a subsidiary many observers had

considered a lost cause. After returning to Dearborn, Reith rejoined

Crusoe’s staff, certain that he was bound for bigger and better things.

Crusoe and Reith expanded on the Davis Book’s recommendations with a

remarkably ambitious new plan to expand the company from three

automotive divisions (Ford, Lincoln-Mercury, and Special Products) to

five, including separate Lincoln and Mercury divisions and a new

mid-priced division known as “E-Car” (for “experimental”), positioned

between Ford and Mercury. The divisions would share three basic body

shells: one for Ford and the low-end E-Car, one for the high-end E-Car

and the cheaper Mercury, and one for the big Mercury and Lincoln.

The new divisions were not intended simply as a paper shuffle; the

principal motivation was to allow Ford to expand its dealer body. At the

time, Ford had only about half as many U.S. dealer franchises as

General Motors, which put definite limits on how many cars Ford could

expect to sell. That was particularly true of Mercury. Although Ford’s

mid-priced brand was doing quite well in the early and mid-fifties, its

total sales amounted to barely a third of GM’s Buick-Oldsmobile-Pontiac

trio — which together averaged around 1.2 million units a year — in part

because Lincoln-Mercury had far fewer dealers than Buick, Oldsmobile,

and Pontiac.

In their presentation to the board on April 15, Crusoe and Reith

claimed their plan would increase Ford Motor Company’s total market

share by almost 20 percent in the next six years. Some senior Ford

executives, notably John Davis, objected to the plan, arguing that

trying to move Mercury upscale and shift its existing buyers to a new

brand would be a disaster. Some of the staunchest opposition came from

McNamara, who argued that the plan was so expensive that it wouldn’t

show a profit for years. (Tom Bonsall suggests that McNamara may have

seen the plan as an unwelcome power play by Reith.)

Despite those criticisms, the board of directors — including Breech —

unanimously approved the Crusoe-Reith plan. The formal reorganization

of divisions took place three days later, separating Mercury and

Lincoln, renaming the existing Special Products Division Continental

Division, and adding a new Special Products Division to build the

still-unnamed E-Car. Jack Reith became general manager of Mercury, which

Bonsall suspects was Reith’s goal all along. The new general manager of

the E-Car division was Dick Krafve, who, ironically, had opposed the

Crusoe-Reith plan, arguing that the E-car should be a Mercury. Despite

his reservations, Krafve accepted the assignment and vowed to do his

best.

“AN OLDSMOBILE SUCKING A LEMON”

By the time the board approved the Crusoe-Reith plan, styling

development of what would become the E-Car had been under way for almost

a year, led by a young designer named Roy Brown, Jr., previously part

of Gene Bordinat’s Mercury studio. In an interview with Dave Crippen in

the eighties, Bordinat recalled that Brown was ecstatic about his new

assignment: To be able to set the direction for a completely new car was

every designer’s dream.

Brown’s team had several directives for the new car’s design, of

which the most important was the imperative to make the car immediately

recognizable from any angle. Distinctive styling was critical to the

E-Car’s commercial prospects, since it would be using body shells shared

with other Ford Motor Company models.

The Edsel’s “horse collar” grille, designed

by stylist Jim Sipple, was inspired in part by Alfa Romeo. This

four-door hardtop is a 1958 Edsel Ranger, the base EF (Ford-bodied)

model. Rangers and Pacers were 213.1 inches (5,413 mm) long on a

118-inch (2,997mm) wheelbase; the larger Mercury-based Corsair and

Citation were 218.8 inches (5,558 mm) long on a 124-inch (3,150mm)

wheelbase, tipping the scales at over 4,200 lb (1,920 kg). The big

Edsels were actually larger than the low-end Mercurys that shared their

body shell. (Photo © 2005 Robert Nichols; used with permission)

The Edsel’s “horse collar” grille, designed

by stylist Jim Sipple, was inspired in part by Alfa Romeo. This

four-door hardtop is a 1958 Edsel Ranger, the base EF (Ford-bodied)

model. Rangers and Pacers were 213.1 inches (5,413 mm) long on a

118-inch (2,997mm) wheelbase; the larger Mercury-based Corsair and

Citation were 218.8 inches (5,558 mm) long on a 124-inch (3,150mm)

wheelbase, tipping the scales at over 4,200 lb (1,920 kg). The big

Edsels were actually larger than the low-end Mercurys that shared their

body shell. (Photo © 2005 Robert Nichols; used with permission)

That push for uniqueness was responsible for most of the E-Car’s

controversial styling features. The vertical grille, which would inspire

a host of imaginatively unflattering epithets, was chosen because no

other American car of the time had a similar front-end treatment. The

same logic inspired the dramatic gullwing taillights and side scallops.

Whatever its other virtues, the E-Car did not look like anything else on

the road.

When it was originally designed, the E-Car was bigger than the

standard Mercury, but after the approval of the Crusoe-Reith plan,

Brown’s team rescaled their design for two different versions: the

Ford-bodied (EF) standard models and the Mercury-bodied (EM) big cars.

That decision was made fairly late in the design process, so there was

little stylistic difference between the EF and EM versions other than

trim and overall dimensions.

Roy Brown presented a full-size fiberglass model of an EM convertible

to the board of directors on August 15, 1955, receiving a standing

ovation led by Ernie Breech. The design was approved precisely three

months after the approval of the Crusoe-Reith plan.

MOTIVATIONAL RESEARCH

In late 1955, Special Products Division marketing specialist David

Wallace ordered yet another marketing study, this one an in-depth

analysis of prospective buyers conducted by Columbia University’s Bureau

of Applied Social Research. This study, which involved 1,600 interviews

in Peoria, Illinois, and San Bernardino, California, went well beyond

the typical marketing survey, attempting to quantify the psychological

motivations of new-car buyers.

Motivational research of this kind was a new idea in the fifties. The

hipper ad agencies had embraced it, but conservative businesses viewed

it with great suspicion and it had drawn the ire of social critics like

Vance Packard, who saw motivational research as an insidious force,

manipulating people into buying things they neither wanted nor needed.

Many Detroit executives dismissed it as mumbo jumbo.

The Columbia study later sparked considerable controversy and some

critics even blamed it for the E-Car’s eventual failure. Although the

study’s questions and methodology were a bit peculiar, the conclusions

mostly reiterated the previous studies, suggesting that the E-Car’s

target audience should be upwardly mobile families and young executives.

In any event, the study’s actual impact on E-Car product planning

appears to have been very limited. It seems that the study’s real

purpose was not so much to draw new conclusions as to rationalize

choices that had already been made months months or years earlier.

The Edsel’s gullwing taillight treatment is

almost as dramatic as its grille, presaging the rear-end styling of the

following year’s Chevrolet. Edsel running gear and suspension were very

conventional — double wishbones in front, Hotchkiss drive

in back — but it was one of the first Ford products with self-adjusting

brakes. (Photo © 2005 Robert Nichols; used with permission)

The Edsel’s gullwing taillight treatment is

almost as dramatic as its grille, presaging the rear-end styling of the

following year’s Chevrolet. Edsel running gear and suspension were very

conventional — double wishbones in front, Hotchkiss drive

in back — but it was one of the first Ford products with self-adjusting

brakes. (Photo © 2005 Robert Nichols; used with permission)

NAMING THE EDSEL

The Columbia study did not address what became the most contentious

part of the E-Car’s development: selecting a name. Early on, Dick Krafve

had suggested “Edsel,” thinking it would be an appropriate way to honor

the man who had brought Ford to the mid-priced market in the first

place, but the Ford family had not been enthusiastic.

The naming process, which took months, ultimately involved the

Special Products Division marketing staff; a local market research firm;

and the division’s new ad agency, Foote, Cone & Belding (FCB).

David Wallace and product planner Bob Young even asked the well-known

Modernist poet Marianne Moore to suggest some names, which yielded

ludicrous results; among Moore’s suggestions were “Andante Con Moto,”

“Mongoose Civique,” and “Utopian Turtletop.” (Tom Bonsall notes that

contrary to popular belief, Ford did not actually

hire Moore, although Young and Wallace did send her flowers to thank her for her efforts.)

Special Products PR director Gayle Warnock presented the more

rational name suggestions to the board in mid-1956. Ernie Breech

summarily rejected all of the choices and asked to hear some of the

runners-up. Eventually, they came back to “Edsel” and Breech suggested

they call the E-Car that. Dick Krafve pointed out Henry Ford II’s

previous opposition to the name, but Breech said he would talk to Henry

personally. (In later years, Breech tried to downplay his role in this

decision, claiming that Crusoe had talked him into it. However, it was

Breech who convinced Henry Ford to secure the reluctant approval of the

Ford family for the use of the Edsel name.)

Warnock was very uncomfortable with the Edsel name, which was not

exactly mellifluous; Warnock later claimed it cost the E-Car 200,000

sales. Moreover, the division had just wasted months of work and

thousands of dollars trying to come up with new names just to come back

to Dick Krafve’s original idea. That pattern was becoming an overriding

theme of the entire E-Car program.

The work done on alternative name choices was not wholly in vain.

Some of the rejected names became the Edsel’s initial trim series: The

smaller EF (Ford-based) models were the Ranger and Pacer, supplemented

by Roundup, Villager, and Bermuda station wagons while the EM

(Mercury-based) cars were named Corsair and Citation.

Ford announced the Edsel name to the public in a press statement on

November 19. With the announcement, Special Products Division became the

Edsel Division.

THE CRUSOE-REITH PLAN COMES APART

By the time of the Edsel announcement, the Crusoe-Reith plan was already fraying.

The first warning sign was the demise of the original plan to share

bodies between Mercury and Lincoln. In the fall of 1955, however, Earle

MacPherson had suggested switching the 1958 Lincoln to unibody

construction and building it in Ford’s new Wixom, Michigan, plant

alongside the 1958 Ford Thunderbird.

Wixom did not have sufficient capacity to build Mercurys and no other

Ford plant was then capable of handling unitized construction.

As a result, the ’58 Lincoln would once again have a stand-alone body

and the so-called “Super Mercury,” a crucial part of Jack Reith’s plan

to take Mercury upscale, would have to settle for a stretched version of

the standard Mercury body. Reith protested, but MacPherson, by then

Ford’s vice president of engineering, had more clout. The board approved

the unitized Lincoln.

To make matters worse, the Continental Division had turned out to be

an expensive flop. Its first product, the $10,000 Mark II coupe, had

been released in November 1955 to mild critical acclaim and meager

sales.

Although production continued until August 1957, Ford shuttered

the division in July 1956 and rolled its operations back into Lincoln’s.

In November 1956, Edsel inherited the former Continental offices. It

was not an auspicious omen.

In May 1957, the Crusoe-Reith plan lost one of its principal

architects: Lewis Crusoe suffered a heart attack that forced him into

early retirement. Robert McNamara, who was still strongly opposed to the

whole plan, replaced Crusoe as group VP of car and truck operations.

Reith himself was the next casualty. That August, he was fired as

general manager of Mercury and Lincoln and Mercury were reintegrated

under the leadership of James Nance, formerly the head of Studebaker-Packard. With Reith’s exist, the only significant remnant of the Crusoe-Reith plan was the Edsel.

Part of the rationale for the Edsel’s

overwrought styling was to distinguish it from its less-expensive Ford

sibling — the 1958 Pacers pictured above share the same body shell as

the 1958 Ford Fairlane. (Photo © 2005 Morven; used under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

Part of the rationale for the Edsel’s

overwrought styling was to distinguish it from its less-expensive Ford

sibling — the 1958 Pacers pictured above share the same body shell as

the 1958 Ford Fairlane. (Photo © 2005 Morven; used under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

THE EDSEL IS BORN

Edsel pilot production began on April 15, 1957, exactly two years

after the board approved the Crusoe-Reith plan and about a week after

the first dealership franchise agreements were signed. Full production

began in July.

Early on, there had been a tentative plant to give the Edsel division

its own factory, but the board decided instead to expand the capacity

of several existing plants and build the Edsel alongside its Ford and

Mercury cousins. The sales force was told that this was a temporary

measure and that Edsel would eventually have a factory of its own.

Building the Edsel on the same lines as Fords and Mercurys may have

made financial sense, but it was disastrous for quality control. Despite

their structural commonality with the contemporary Ford and Mercury,

Edsels had unique trim and many unique components, which greatly

complicated assembly line operations and created many opportunities for

error. Shared production also generated considerable resentment among

factory workers, who were annoyed at having their jobs made more

difficult by another division’s products. Ford quality was already

sub-par that year and Edsels were often even worse, with some cars

arriving at dealers in unsalvageable condition.

That was apparently Robert McNamara’s conclusion about the entire

Edsel operation. Around the time the first Edsels went on sale, McNamara

allegedly told FC&B’s Fairfax Cone that Ford already planned to

phase out the division.

All 1958 Edsels had V8 engines; a six became

optional in 1959. This 1958 Pacer hardtop coupe has a 361 cu. in. (5,902

cc) V8, part of the new FE (Ford-Edsel) series that spawned the later

390 (6,391 cc) and 427 (6,986 cc) engines. The Edsel version, called

E-400, was rated 303 gross horsepower (226 kW) with a single four-barrel

carburetor. The 1958 Corsair and Citation used the E-475, a 410 cu. in.

(6,722 cc) version of the big MEL-series engine shared with Mercury and

Lincoln, with 345 gross horsepower (257 kW). (Photo © 2007 Redsimon; used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license)

All 1958 Edsels had V8 engines; a six became

optional in 1959. This 1958 Pacer hardtop coupe has a 361 cu. in. (5,902

cc) V8, part of the new FE (Ford-Edsel) series that spawned the later

390 (6,391 cc) and 427 (6,986 cc) engines. The Edsel version, called

E-400, was rated 303 gross horsepower (226 kW) with a single four-barrel

carburetor. The 1958 Corsair and Citation used the E-475, a 410 cu. in.

(6,722 cc) version of the big MEL-series engine shared with Mercury and

Lincoln, with 345 gross horsepower (257 kW). (Photo © 2007 Redsimon; used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license)

SELLING THE EDSEL

The 1958 Edsels debuted with great fanfare on September 4, 1957. Its

launch was preceded by months of teaser ads and grandiose claims by Ford

management. In January, Ford had announced that the Edsel would be a

radical new design, using many new production techniques. Dick Krafve

told the press that Edsel expected to sell 200,000 units in the first

year.

The automotive press was scrupulously polite about the Edsel’s looks,

but the public was far less kind. The Edsel’s grille immediately became

the punchline of many off-color jokes, which compared it to everything

from a horse collar to female anatomy. Not since the “coming or going”

Studebaker of 10 years earlier had a new car’s styling been the subject

of so much public ridicule. Edsel’s frequently poor early quality

control did nothing to help.

The dashboard of a 1958 Edsel Ranger. The

left-most pod is a compass; on upper-series Edsels, it was filled with a

tachometer. The dials to the right of the steering column are a clock

and the heater controls. The left bank of switches control the lights,

antenna, and courtesy lights, while the right bank (not visible)

controls the heater fan, wipers, and cigarette lighter. The buttons on

the steering wheel bus are the “Teletouch” transmission controls. Unlike

the pushbutton transmissions used by contemporary Chrysler products,

Teletouch was electrically operated. It was a neat idea, but it proved

grievously unreliable and was dropped at the end of the model year.

(Photo © 2005 Robert Nichols; used with permission)

The dashboard of a 1958 Edsel Ranger. The

left-most pod is a compass; on upper-series Edsels, it was filled with a

tachometer. The dials to the right of the steering column are a clock

and the heater controls. The left bank of switches control the lights,

antenna, and courtesy lights, while the right bank (not visible)

controls the heater fan, wipers, and cigarette lighter. The buttons on

the steering wheel bus are the “Teletouch” transmission controls. Unlike

the pushbutton transmissions used by contemporary Chrysler products,

Teletouch was electrically operated. It was a neat idea, but it proved

grievously unreliable and was dropped at the end of the model year.

(Photo © 2005 Robert Nichols; used with permission)

Aside from its styling and assembly quality, the Edsel’s fundamental

problem was the worrisome ambiguity of its market position. Although

Jack Reith’s long-awaited big Mercury — now called Park Lane — also

debuted that fall, the original plan to take Mercury upmarket did not

materialize. As a result, the Edsel straddled the Mercury line rather

than fitting between Ford and Mercury. Worse, there was

still a gap of nearly $700 between the most expensive Mercury Park Lane and the cheapest Lincoln.

If the Edsel had debuted two years earlier, it might have done

somewhat better, but it had the misfortune to arrive just as the economy

began to sink dramatically. The stock market had taken a nosedive back

in June and by September, the U.S. economy was entering a full-fledged

recession. Moreover, buyers had apparently had their fill of overwrought

styling just Detroit’s new models hit new heights of rococo gimmickry.

As a result, sales of most mid-priced cars immediately tanked, with some

makes falling by more than 30%. Mercury’s total volume plunged from

about 286,000 for the 1957 model year to about 153,000 for 1958. Edsel’s

first-year total was only 63,110, less than a third of Ford’s

optimistic sales projections.

FULL RETREAT

By the end of 1957, it was clear that Edsel sales did not justify the

expense of maintaining a separate division. On January 14, 1958, it was

rolled into Lincoln-Mercury, which was renamed the

Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln Division with Jim Nance as general manager.

Richard Krafve resigned from Ford a year later; he went on to become the

president of Raytheon.

The 1959 Edsel was, if anything, less

ostentatious than its overwrought ’59 Ford sibling, retaining the

vertical grille concept in a much less confrontational form. If the 1958

Edsel had looked like this, it might have sold better than it did.

The 1959 Edsel was, if anything, less

ostentatious than its overwrought ’59 Ford sibling, retaining the

vertical grille concept in a much less confrontational form. If the 1958

Edsel had looked like this, it might have sold better than it did.

Ford tried hard to put a positive spin on Edsel’s weak debut. A June

1958 press release admitted that first-year sales were disappointing,

but spoke optimistically about the marque’s future. In fact, Edsel’s

fate beyond 1960 was already in considerable doubt.

In August 1958, James Nance was ousted as the head of

Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln. His replacement was Ben Mills, another of the

Whiz Kids. Mills announced that the 1959 Edsel line would be pared down

to the Ranger, Corsair, and Villager station wagon, all using the

smaller Ford shell. The bigger EM (Mercury-based) models and the big

MEL-series engine were dropped. The Ranger traded its previously

standard 361 cu. in. (5,902 cc) FE-series engine for the 292 cu. in.

(4,778 cc) Y-block; Ford’s 223 cu. in. (3,653 cc) “Econo-Six” was now

optional. The optional automatic transmission on smaller-engined Edsels

was now the Mile-O-Matic, essentially the same as the new two-speed

Fordomatic. The unreliable Teletouch pushbuttons were long gone.

Most 1959 Edsels had smaller engines than

their 1958 counterparts. The Ranger had the 292 cu. in. (4,778 cc)

Y-block with 200 hp (149 kW), while the standard engine on the Corsair

was now the 332 cu. in. (5,436 cc) FE with 225 hp (168 kW). The ’58

Ranger’s 361 cu. in. (5,902 cc) four-barrel engine, renamed “Super

Express,” was optional; it again had 303 gross horsepower (226 kW).

Four-door Ranger sedans like this one were the most popular 1959 Edsel;

they had a base price of $2,684 and accounted for 12,814 sales.

Most 1959 Edsels had smaller engines than

their 1958 counterparts. The Ranger had the 292 cu. in. (4,778 cc)

Y-block with 200 hp (149 kW), while the standard engine on the Corsair

was now the 332 cu. in. (5,436 cc) FE with 225 hp (168 kW). The ’58

Ranger’s 361 cu. in. (5,902 cc) four-barrel engine, renamed “Super

Express,” was optional; it again had 303 gross horsepower (226 kW).

Four-door Ranger sedans like this one were the most popular 1959 Edsel;

they had a base price of $2,684 and accounted for 12,814 sales.

The 1959 Edsel’s styling was toned down considerably from its first

year. Contrary to popular belief, the more conservative look was not a

reaction to the public ridicule; Roy Brown’s team had designed the ’59

in late 1956 and early 1957, well before the 1958 Edsel went on sale.

The new styling was much more conservative than the ’58, although it was

also more ordinary, making the Edsel look more like the facelifted Ford

it was.

Despite the smaller engines and toned-down styling, the 1959 Edsel

was more expensive than the ’58, by as much as $120. The higher prices,

combined with the still-rocky state of the economy and lingering buyer

doubts about the Edsel’s quality, made for dismal sales. The total for

the 1959 model year sank to about 45,000, just behind Chrysler’s equally

moribund DeSoto.

Roy Brown, who was transferred in April 1958 to Ford of England, also

developed full-size clay models for the 1960 Edsel. However, Robert

McNamara decided that Edsel sales didn’t justify the tooling investment.

Stylist Bud Kaufman was ordered to create a cheaper alternative design

with a minimal tooling budget of less than $10 million — small change by

Detroit standards. It meant that the 1960 Edsel would be little more

than a badge-engineered Ford.

All 1959 Edsels shared the body shell of the

’59 Ford. Although the wheelbase was stretched from 118 inches (2,997

mm) to 120 inches (3,048 mm), the 1959 Edsel Ranger was slightly shorter

than the ’58, 210.9 inches (5,357 mm) overall. Car Life,

testing a four-door hardtop Ranger with the same powertrain as this

car, recorded a 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) time of just under 11 seconds with

gas mileage of about 14 mpg (around 17 L/100 km), average performance

for the time.

All 1959 Edsels shared the body shell of the

’59 Ford. Although the wheelbase was stretched from 118 inches (2,997

mm) to 120 inches (3,048 mm), the 1959 Edsel Ranger was slightly shorter

than the ’58, 210.9 inches (5,357 mm) overall. Car Life,

testing a four-door hardtop Ranger with the same powertrain as this

car, recorded a 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) time of just under 11 seconds with

gas mileage of about 14 mpg (around 17 L/100 km), average performance

for the time.

PLAN B: THE COMET

By May 1958, Jim Nance and Ben Mills were thinking about taking Edsel

in a completely new direction. Ford was then busily developing a new

compact model, which emerged as the 1960 Ford Falcon.

With small-car sales booming since the start of the recession,

Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln dealers were screaming for a compact of their own.

Nance and Mills decided that an M-E-L compact would make most sense as

an Edsel, which would preserve Mercury and Lincoln’s market position and

finally give the Edsel brand a unique product.

The board of directors approved the Edsel compact proposal, dubbed

“Edsel B,” in September 1958, shortly after Nance’s departure. The Edsel

B, later named Comet, would share the Falcon’s body and running gear,

but it would be somewhat bigger and a little more expensive, allowing a

higher level of trim and features. The plan was for the Comet to

supplement the larger Edsels for 1960 and then to replace them entirely

by 1961, demoting the E-Car from mid-priced model to upscale economy

car.

A final-year Edsel Ranger shows off Bud

Kaufman’s new styling. Not quite visible is the split grille that bears a

distinct (if probably coincidental) resemblance to the 1959 Pontiacs. (Photo © 2010 Fletcher6; used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

A final-year Edsel Ranger shows off Bud

Kaufman’s new styling. Not quite visible is the split grille that bears a

distinct (if probably coincidental) resemblance to the 1959 Pontiacs. (Photo © 2010 Fletcher6; used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

In any case, Edsel didn’t make it that far. The 1960 models debuted

on October 15, but dealers were extremely reluctant to order them. In

the first month, there were only 2,400 orders from nearly 1,500

franchises. By then, many Edsel dealers had either given up or gone

under, and most survivors also had Ford and/or Lincoln-Mercury

franchises. They had little interest in taking a chance on yet another

Edsel.

On November 19, Ford announced that it was pulling the plug. Sales

for the abbreviated 1960 model year amounted to 2,846, bringing total

Edsel production to 110,847 cars in three model years. Ford offered

hefty dealer incentives to clear stocks of unsold cars.

If Edsel had still been a separate division at that point, the Comet

might have died with it, but Ben Mills saw no reason to throw away a

promising new product. The Comet went on sale through Lincoln-Mercury

dealers in March 1960, about four months after the Falcon. (Although

contemporary reviewers tended to describe it as a Mercury, it was

technically a separate make with no other marque identification.) In its

first year, the Comet sold over 116,000 units, exceeding the entire

three-year total of its late parent. The Comet’s success inspired the

very successful intermediate Ford Fairlane and a whole genre of midsize cars.

The original Comet was styled by Bud Kaufman,

marrying a stretched version of the Falcon body with a formal roof

inspired by the 1959 Ford Galaxie. The Comet shared the Falcon’s 144 cu.

in. (2,365 cc) and 170 cu. in. (2,780 cc) sixes, but it rode a 5.5 inch

(140 mm) longer wheelbase and was about 100 lb (45 kg) heavier, making

it even slower than its Ford cousin. (Photo © 2007 Infrogmation; used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license)

The original Comet was styled by Bud Kaufman,

marrying a stretched version of the Falcon body with a formal roof

inspired by the 1959 Ford Galaxie. The Comet shared the Falcon’s 144 cu.

in. (2,365 cc) and 170 cu. in. (2,780 cc) sixes, but it rode a 5.5 inch

(140 mm) longer wheelbase and was about 100 lb (45 kg) heavier, making

it even slower than its Ford cousin. (Photo © 2007 Infrogmation; used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license)

POSTMORTEM

There is no doubt that Ford lost a lot of money on the Edsel fiasco.

The most commonly cited figure is $250 million (equivalent to almost

$1.9 billion in 2010 dollars), which was the cost Ford announced for

launching the new model. Ford spent about $100 million on marketing and

the overhead costs of running Edsel as a separate division; as a point

of comparison, Ford said that re-consolidating Lincoln and Mercury in

1957 saved about $80 million a year in administration and overhead

expense. The estimated $150 million spent on factory expansion was

obviously not a total loss, since Ford continued to use that capacity

after the Edsel was gone.

Regardless of the actual dollar losses, the whole debacle had other

costs. First, we suspect that a fair number of the sales Edsel did

achieve came at the expense of Mercury. The first Park Lane sold poorly

and most Mercury sales in 1958-1959 were low-end models that competed

directly with Edsel in size and price. Second, not sharing bodies

between Mercury and Lincoln proved to be very expensive. The 1958-1960

Lincolns also lost money and Lincoln came very close to cancellation,

although it was saved by the new 1961 Continental.

Third, and perhaps most seriously, Ford never actually plugged the gap

between Mercury and Lincoln, so the E-Car’s original objective remained

unfulfilled.

Over the years, historians have laid the blame for the Edsel’s

failure on many things: the styling, the name, the market research, the

poor timing of its debut. There’s some truth to each of those

conclusions, but we think that the E-Car’s greatest failing was that

Ford lost sight of what it was supposed to be. The initial goal —

filling a hole in the lineup — was straightforward enough, but it was

completely overshadowed by nine years of political gamesmanship. When

the E-Car finally appeared, it was redundant. Even if the market had

been better, the best it could have done was to eat away even more at

Mercury’s market share. The Edsel didn’t simply fail; it never had a

chance.

The Edsel remained a sore subject within Ford for many years after

its demise. Lee Iacocca, who became general manager of Ford Division in

1960, convinced Henry Ford II to cancel the FWD subcompact Cardinal by

warning him that it would be another E-Car. The Edsel’s failure was

particularly bitter for Henry Ford; not only had it lost a huge amount

of money, it had made a joke of his late father’s name. Edsel — both the

car and the man — deserved better.

Source: ateupwithmotor.com

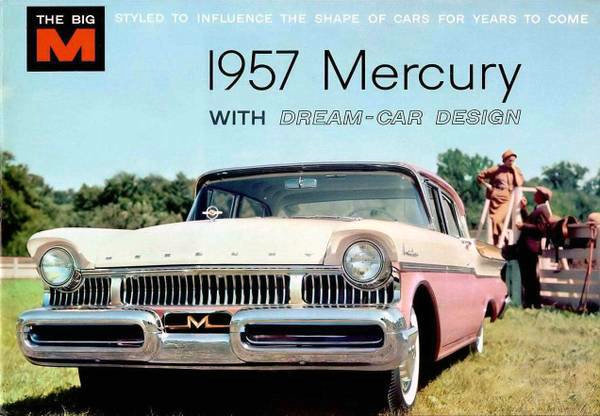

This is an opportunity to stand out from the crowd! As the seller notes, there are a lot of more mainstream ’57 cars

This is an opportunity to stand out from the crowd! As the seller notes, there are a lot of more mainstream ’57 cars out there, such as Fords and Chevrolets, but very few of these spectacular Mercurys. This Monterey is listed for sale here on craigslist for $7,500 and is located in Avinger, Texas. This car has the 312 V8, making 290 horsepower in this applicationimage: http://cdncache-a.akamaihd.net/items/it/img/arrow-10x10.png

out there, such as Fords and Chevrolets, but very few of these spectacular Mercurys. This Monterey is listed for sale here on craigslist for $7,500 and is located in Avinger, Texas. This car has the 312 V8, making 290 horsepower in this applicationimage: http://cdncache-a.akamaihd.net/items/it/img/arrow-10x10.png .

It also has power steering, power disc brakes, and, unusually, air

conditioning. There are some rusty parts around the edges, but as

a whole the body seems relatively solid. I’m not sure I’d leave the new

custom wheels; I think steel wheels and small caps would be ideal for

this car, but that’s me.

.

It also has power steering, power disc brakes, and, unusually, air

conditioning. There are some rusty parts around the edges, but as

a whole the body seems relatively solid. I’m not sure I’d leave the new

custom wheels; I think steel wheels and small caps would be ideal for

this car, but that’s me. As you can see from this ad, Mercury liked this color scheme too. Just look at that “Dream Car

As you can see from this ad, Mercury liked this color scheme too. Just look at that “Dream Car Design!” Is this pink and white cruiser your dream car?

Design!” Is this pink and white cruiser your dream car?